A History and Evolution of Value Investing

Introduction

Disciplined value investors have shared a core ethos for centuries: buy quality assets at discounted valuations. The methods employed to reach this objective have evolved, but the strategy remains the same as the first value fund in 1779:

“[this fund favors] solid securities and those that based on decline in their price would merit speculation and could be purchased below their intrinsic values… of which one has every reason to expect an important benefit...”

['Concordia Res Parvae Crescunt' Prospectus]

A few years earlier, Samuel Bosanquet offered similar advice:

"whenever the commodity they mean to speculate in can be bought under their average price [of the last few years], they think they may safely engage, as they have reason to suppose it will rise in order to come up to its usual price…" [1]

He clearly articulates the concept of ‘mean reversion’, a key source of alpha for value investors. If prices are “below their average”, one could speculate as the asset would likely “come up to its usual price”.

Clearly, we have more in common with our investing predecessors than we’d care to admit. That said, this article uncovers the long history of financial analysis, valuation, and technology to better understand the future of investing.

Financial history offers myriad lessons for today’s investors.

First, bubbles and crashes always make for entertaining reading, but conservative investors have also strived to better understand and value financial assets in those same periods. It’s not like every investor acts manically during speculative bubbles!

Second, valuation techniques are only as good as financial data and technology permits. As you will see, differences in these areas divided British and American investors’ approaches to valuation.

Third, technology itself does not make markets more efficient. That’s both good and bad news. Good news because that means more opportunities to buy quality assets at discounted prices. The bad news is we must try as hard as 18th century investors to avoid behavioral errors. It hasn’t become any easier!

This all produces an important takeaway: increased access to information alone is insufficient for good investing. Conducting superior analysis of that information and remaining disciplined is what differentiates great investors. Advances in modern technology and software empower investors to spend more time doing just that.

Early Approaches: Dutch East India Company to the South Sea Bubble

The inception of equity markets stretches back to 1602 in Amsterdam, where investors mostly traded shares of the Dutch East India Co. (VOC). A titan of industry in its day.

The 1688 investing book, Confusions de Confusiones, reveals detailed accounts of trading in Amsterdam and investors’ behavior. We also gain insights on how investors evaluated securities. The excerpts below show Dutch investors viewed equities in relation to fixed income instruments. Their familiarity with interest payments led to a strong emphasis on dividends in the valuation process for equities.

“big capitalists enjoy the dividends from the shares [they own]... They do not care about the movements in the price of the stock... but in the revenues secured through the dividends...”

“the price of [VOC] shares is now 580, it seems to me that they will climb to a much higher price because of the extensive cargoes that are expected from India, because of the good business of the Company, of the reputation of its goods, of the prospective dividends...”

“revenue from fixed investments [bonds] at fixed interest becomes less... [so] even the wealthiest men are forced to buy stocks... they do not know a more secure investment...”

The South Sea Bubble

Fast forwarding to the 18th century, the British South Sea Company was founded in 1711 for trading slaves with “Spanish America” (Central and South America). But it was Parliament’s 1720 decision to let the South Sea Co. take over the national debt that sent its stock price parabolic.

Why? The company had an innovative plan to reduce Britain’s gorging debt-load: let investors swap their government bonds for South Sea stock (retiring the debt). This “debt-for-equity swap” encouraged promoters – and politicians – to drive up the price of South Sea stock. The higher it went the more debt could be retired! Like Charlie Munger said: “Show me the incentives, and I'll show you the outcome.”

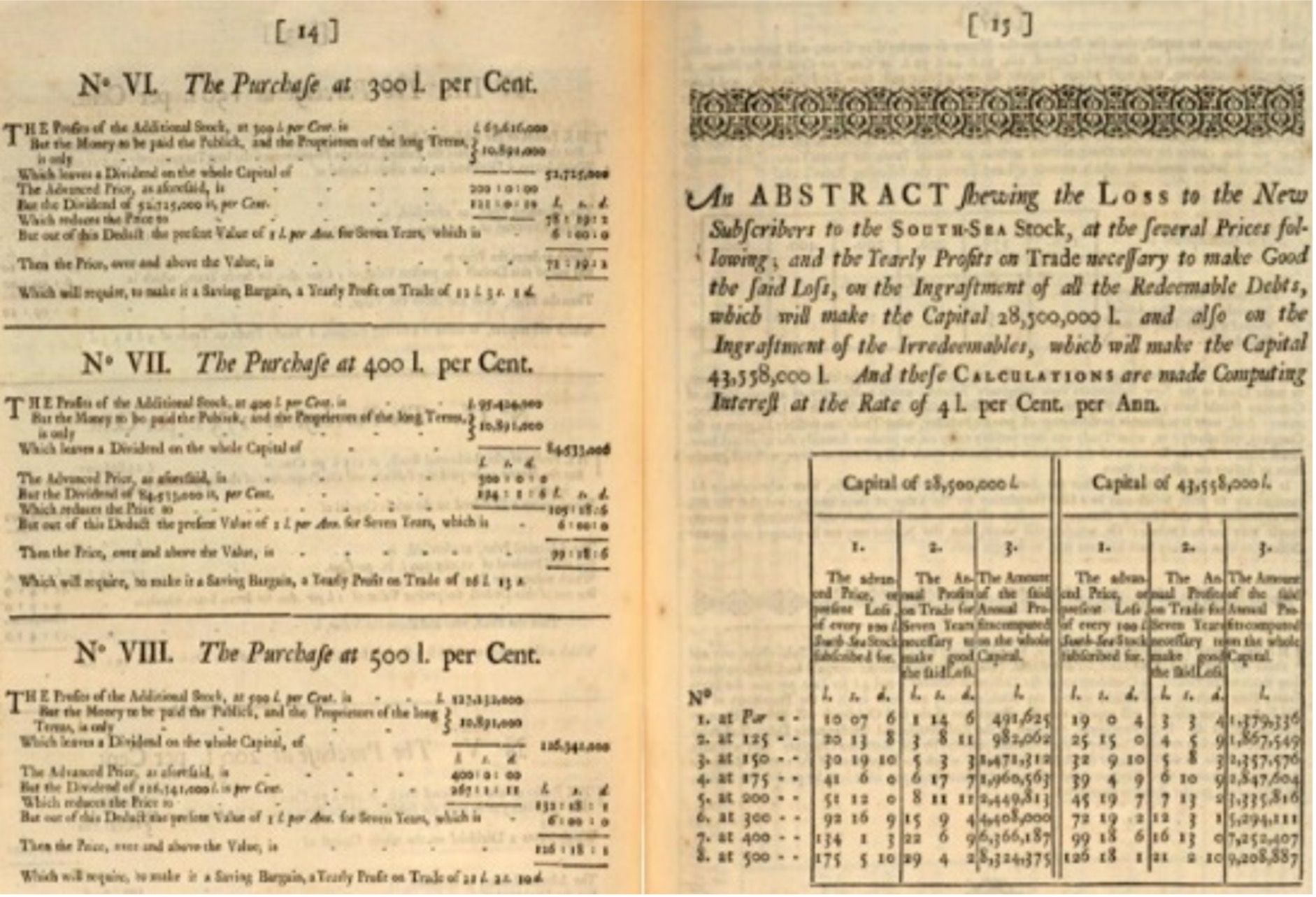

Yet, as Isaac Newton and others hemorrhaged money speculating in South Sea shares, some investors used early valuation techniques to make sense of the madness around them. For example, MP Archebald Hutcheson wrote pamphlets outlining the exorbitant profits and dividends required to justify buying South Sea stock at soaring prices. Hutcheson provided computation tables to help investors determine when buying shares made sense.

"gains of the South Sea Company, in trade, must be immensely great, to make good to the New Subscribers... [but] there is no real Foundation for the present [price of South Sea Stock]... it seems to be the universal opinion... the present price of South Sea Stock is much too high..."

Like in Amsterdam, another 1720 pamphlet described the importance of using dividend yield:

“The main principle on which the whole science of stock jobbing is built, viz. that the benefit of a dividend is always to be estimated according to the rate it bears to the price of the stock, because the purchaser is supposed to compare that rate with the profits he might make of money, if otherwise employed.” [2]

The Wild 1800s: Valuation, Speculation & Industrialization

In the 19th century, investors continued looking to dividends for clues on valuation. Despite two centuries of progress, investors still struggled to access market data and company financials. As Geoffrey Poitras put it, “dividends paid were the most visible and reliable source of information about firm performance.” [3]

Thus, dividends remained the object of investors’ scrutiny. However, new complementary metrics like “dividend cover” emerged to analyze the risk of companies not paying out these coveted dividends. Could a company’s earnings sustain their dividend? Investors wanted to know.

To placate concerns, some prospectuses touted their dividends were “covered five times by profits” [4]. As many companies formed and failed in just a few years, knowing the security of a dividend was crucial.

William Armstrong: An Early Pioneer in Discouted Cash Flow Valuation

William Armstrong was a valuation pioneer. In the mid-1800s, this mining engineer turned valuation consultant used discounted-cash-flow (DCF) analysis to value mining leases and companies going public. [5]

His work fixed an important problem. As we now know, investors in this era valued equities similarly to bonds. Yet, there is a crucial difference: dividends are not fixed like interest payments. Many investors learned that the hard way. But as a mining veteran, Armstrong knew better. Acknowledging the financial uncertainties and volatility endemic to mining, he used risk-adjusted discount rates to determine the net present value (NPV) of future net cash flows. Future cash flows were not guaranteed like interest payments, and Armstrong’s calculations reflected that reality.

A Wave of Changes at the Turn of the Century

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a transformative era in financial history. The U.S. economy took off. Britain’s fell behind. Tickers inundated investors with market data. Bucket shops opened their doors to an army of day-traders. A U.S. ‘merger wave’ created large conglomerates that operated worldwide. Monopolies dominated.

The developments in this period preceded an important transition from dividends to earnings for valuation analyses. There were numerous factors that instigated this shift.

Divergent Paths: America’s Economy Overtakes Britain

After the Civil War, America’s economy ripped. For many reasons. First, the country’s wartime economy revolutionized its transportation infrastructure. America’s railway system only grew faster post-conflict, with railroad track mileage doubling between 1865 – 1873. [6]

Technological innovations in the late 19th century birthed new industries like electrical power, petroleum refining, steel manufacturing, and more. Someone born in the 1840s saw their primary source of light evolve from candles to kerosene lamps, to electric light bulbs. [7]

American industrialization was fueled by these new industries that required factories, manufacturing plants, expansive railway networks, and a large labor force to make it all work. A conveniently timed wave of immigration supplied corporations with cheap labor to make, sell and transport their products.

Meanwhile, Britain’s economic prowess waned in this period for a variety of reasons. Historians have attributed this decline to complacency, lack of domestic investment in new technologies, poor work ethic by the “sons of manufacturers”, and an elitist society that restricted education opportunities. The diverging path of each nation’s economy is depicted below:

The Great Merger Wave of 1895 – 1904

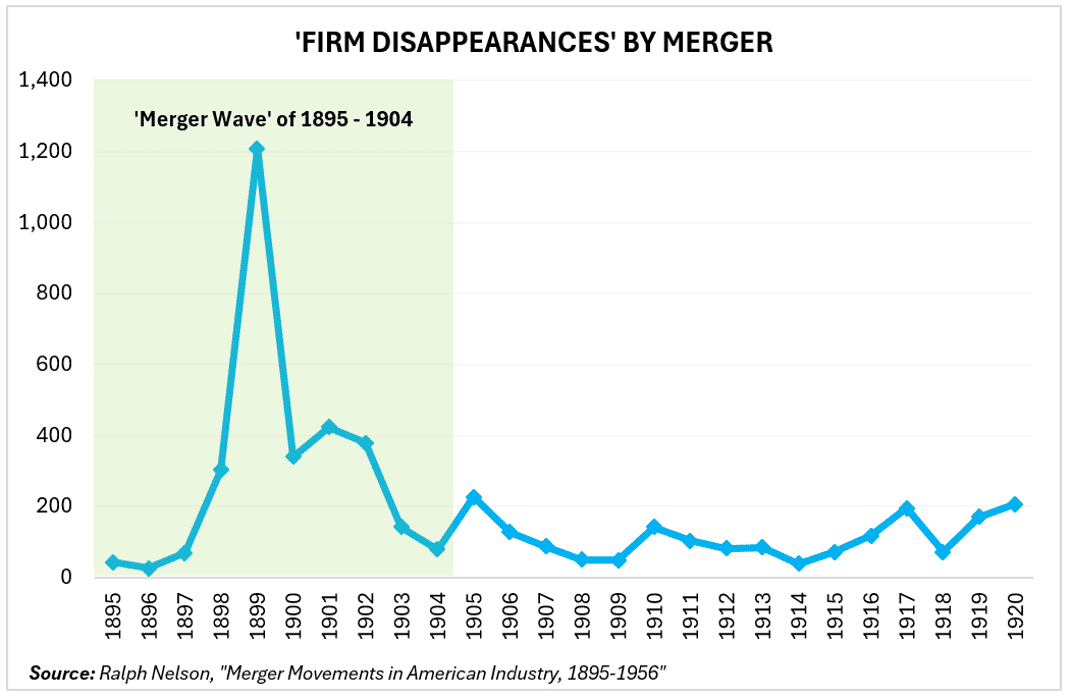

The turn of the 20th century also witnessed America’s first great “merger wave”, where roughly 301 companies “disappeared” through mergers annually. [8]

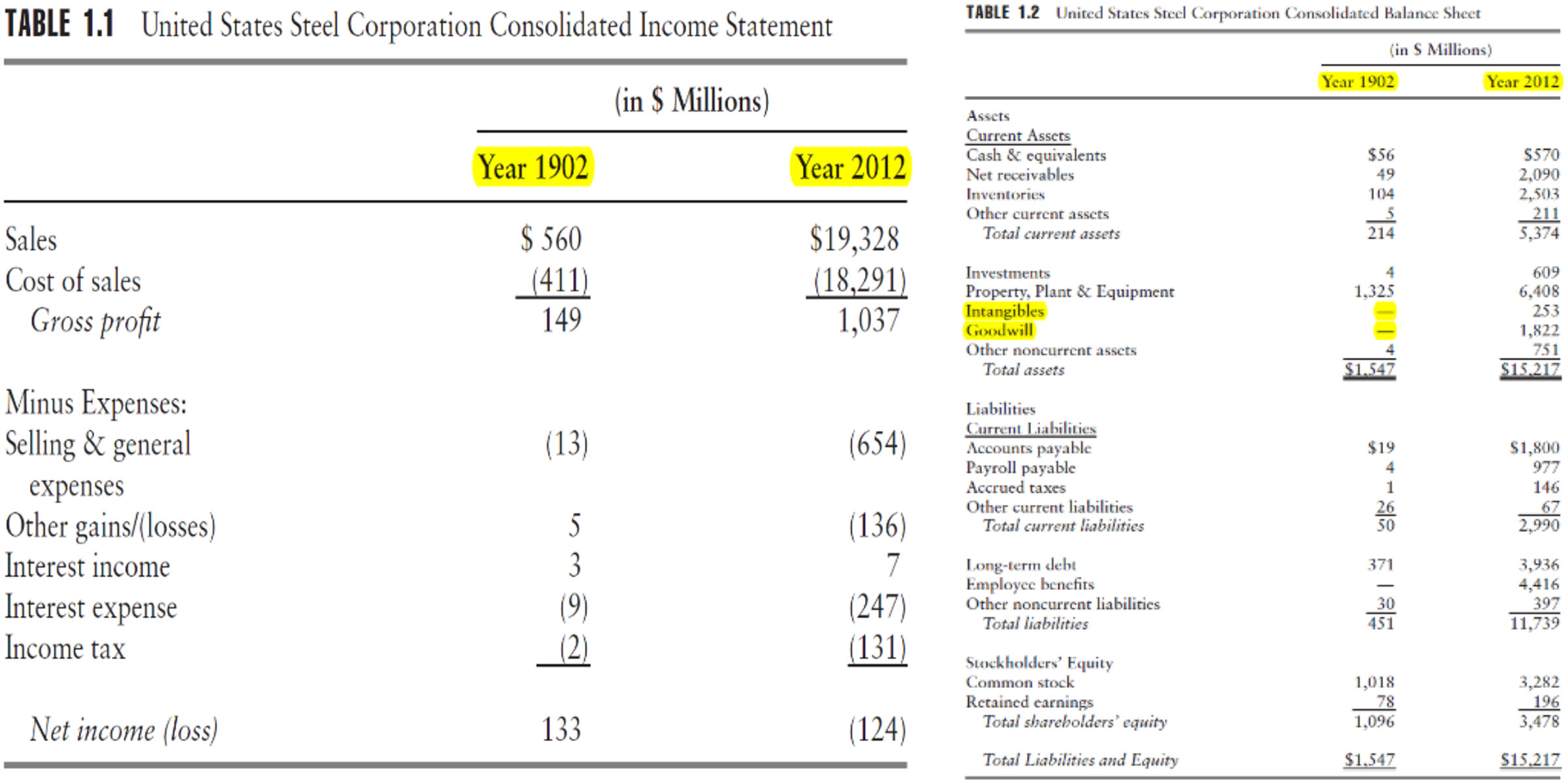

These corporate amalgamations spawned iconic companies like U.S. Steel, American Tobacco, Du Pont, and more. U.S. Steel is particularly important, as the company’s first report to shareholders in 1903 modernized financial statements by sharing a consolidated income statement and balance sheet.

This was a watershed moment for financial reporting in America. Consolidated income statements and balance sheets provided more financial information to investors than ever. As corporate monoliths like U.S. Steel operated in many countries with multiple subsidiaries, reporting detailed financials became necessary. Importantly, U.S. Steel also reported more details on earnings.

In fact, Baruch Lev and Feng Gu directly compared the statements U.S. Steel provided in 1902 and 2012 [9]. As you can see, information provided on the Consolidated Income statement is exactly the same, and only two line items are missing on the 1903 Consolidated Balance Sheet.

These changes aimed to address conglomerates’ increasingly complex operations. In the U.K., where companies did not report consolidated accounts, investors hunted in the dark. One complained:

“[British holding companies’ operations] are often so vast and intricate that no one has any real knowledge of their position except a few directors... It is impossible for even an expert stockbroker to make a reasonable estimate of what such shares are worth, and to buy them is a pig in a poke. It may be a very good pig, but to buy it at a guesswork price is not business.” [9]

Coupled with new disclosure requirements at the NYSE in 1899, American investors were privy to more financial data than ever. Armed with better information, U.S. investors focused on earnings.

Roaring Twenties & Beyond: Earnings, Compound Growth & P/E Ratios

In a January 17, 1925 speech, President Calvin Coolidge eloquently summarized the nation’s mentality:

“After all, the chief business of the American people is business. They are profoundly concerned with producing, buying, selling, investing and prospering in the world.”

And he wasn’t wrong. During World War I, large portions of the American public had their first investing experience through Liberty Bonds. After the war, many of these individuals started dabbling in the stock market. In fact, academic research revealed counties with higher Liberty Bond subscription rates experienced higher levels of stock ownership decades later. [11]

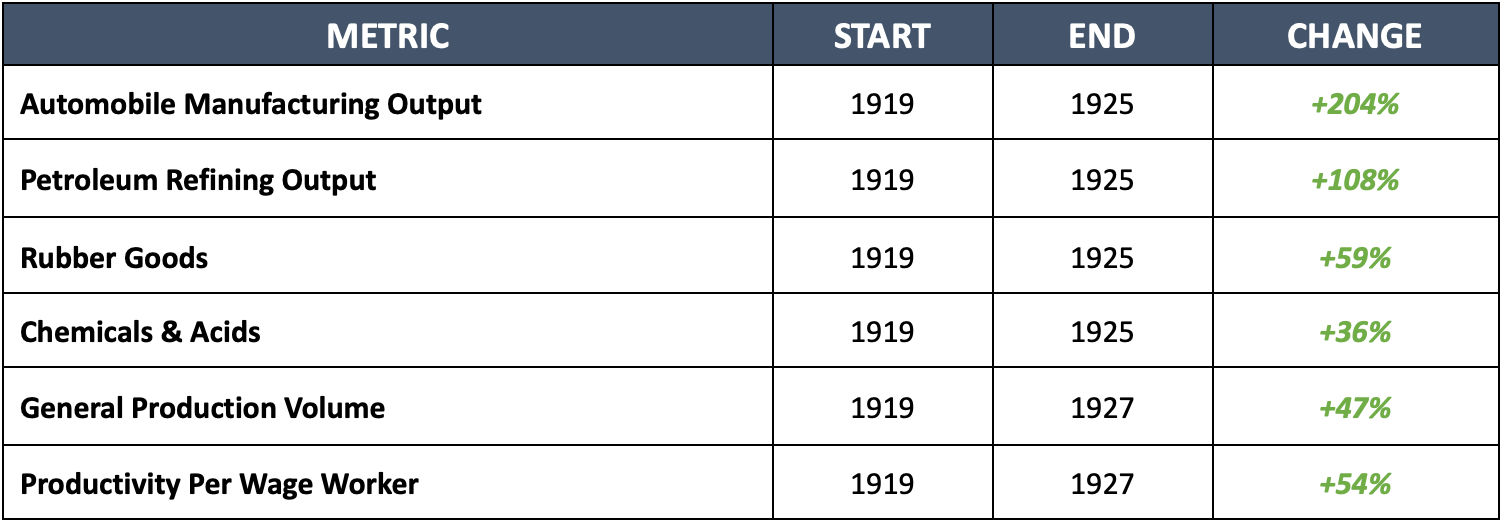

Alongside a growing investor population, business was thriving. Writing in 1930, famed economist Irving Fisher rattled off the following statistics to demonstrate America’s economic prowess [12]:

Amidst extraordinary economic growth and broader stock market participation, Lawrence Smith published his seminal work, Common Stocks as Long Term Investments (1925). His thesis challenged conventional wisdom, arguing common stocks were superior to bonds as long-term investments.

Smith’s reasoning expanded upon the logic that the “safest” bond investments were in companies whose earnings greatly surpassed their debt obligations. Smith wrote “a company whose net earnings are so meager that it can finance necessary expansion or changes only through the creation of new debt” was probably a bad investment.

For companies with earnings far greater than their debt obligations, however, that financial cushion secured bond payments and provided excess capital to reinvest in the business. This capacity for re-investment unlocked the potential for compound growth—leading to increased earnings, appreciating share prices, and, by extension, greater overall returns.

By extrapolating the criteria for "quality" bonds to stock selection, Smith correctly argued that companies with large excess earnings are ideally positioned for sustainable growth. These earnings, reinvested rather than distributed or used to service debt, compounded over time.

“there is a force at work in our common stock holdings which tends ever toward increasing their principal value in terms of dollars, a force resulting form the profitable reinvestment, by the companies involved, of their undistributed earnings.”

Individual investors and analysts in the U.S. latched onto this idea.

The Rise of Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Multiples

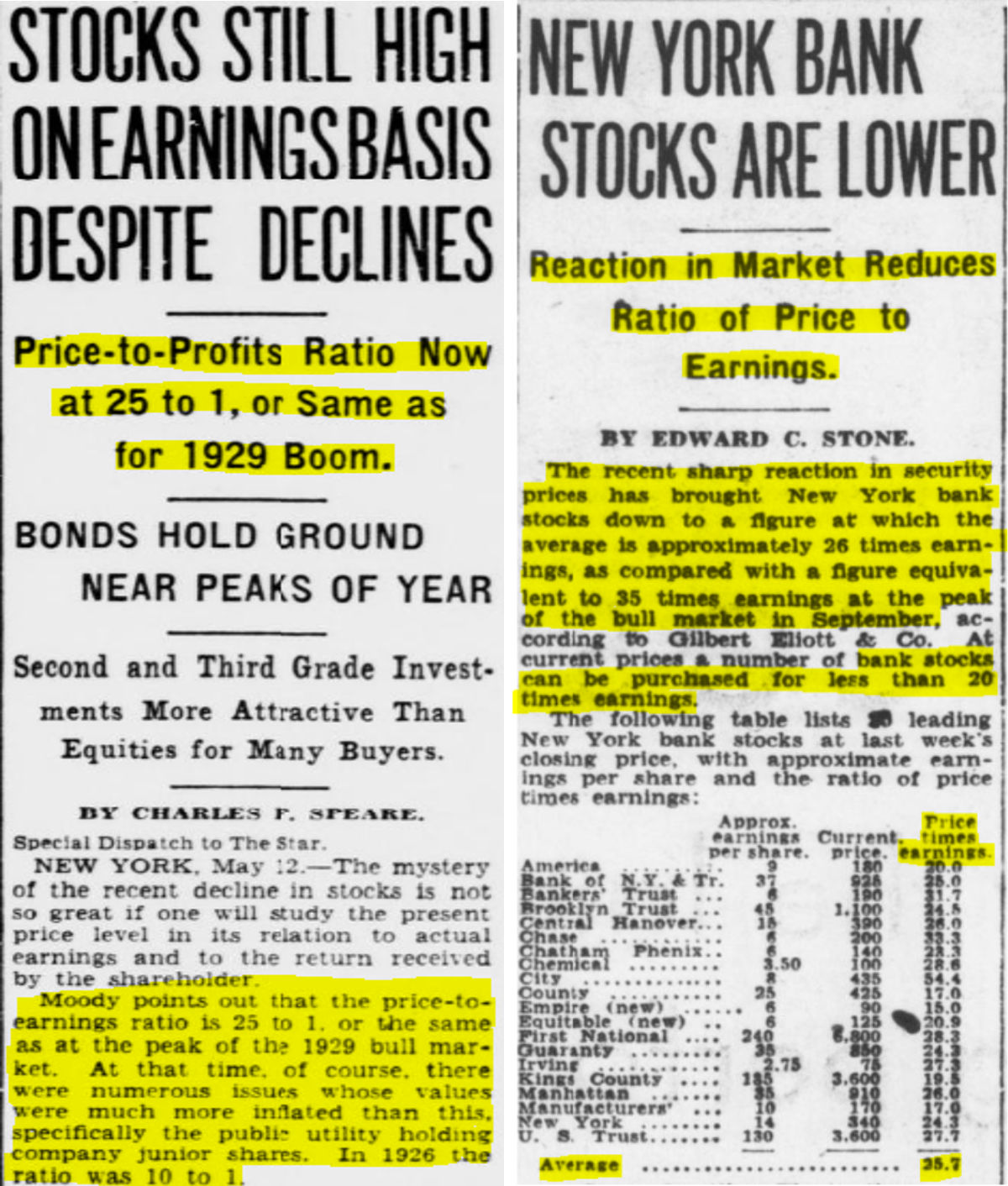

Before long, investors in the 1920s and beyond used Price-to-Earnings multiples for valuing public companies. The newspaper clippings below from 1929 and 1934 highlight the prevalence of earnings ratios in this period. Earnings, not dividends, were the new subject of market scrutiny.

Many investors then divided themselves into two schools of thought. Value investors believed that corporate earnings were relatively stable, and that longer historical averages provided the best basis for current valuations. Companies trading below their long-term averages could be bought at discounted valuations, and investors would profit when they ‘reverted’ to their historical averages.

Growth investors, meanwhile, argued recent earnings were more relevant as technological and societal changes propelled the economy (and corporate profits) to new heights. Fisher argued:

“We are in a dynamic world where the old conception of any fixed ratio of earnings to prices of stocks as a proper ratio must yield to the demands of the shifting scales of industrial effort... new and promising inventions explain high P/E ratios.”

Following the 1929 Crash, value investors fared much better than their Growth counterparts as a dampened stock market provided few exciting “growth” stocks. Instead, value investors like Benjamin Graham and David Dodd welcomed the opportunity to buy quality companies at discounted valuations, betting on their reversion to historical averages.

As time progressed and the Great Depression faded further into the horizon, markets recovered, and value investors profited. For example, U.S. stock market value tripled from 1949 – 1955. From 1955 – 1964, the market doubled. [13]

As the market finally ripped once more, the 1960s ushered in a new wave of exciting growth stocks commanding frothy valuations (Polaroid, IBM, Xerox, etc.). In this environment filled with technological innovations and market exuberance, growth stocks shone brightest.

Discounted Cash Flow Analysis Enters the Conversation

While the simpler P/E ratio remains the most widely used valuation metric, an important development in the 1960s paved the way for future use of DCF modeling: the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The CAPM gave investors a more systematic way to determine appropriate risk-adjusted discount rates (whereas previously the discount rates were much more arbitrary and ad-hoc).

Despite this progress, broader adoption of DCF analysis did not occur until the 1980s and 1990s. This mainly stemmed from the technological requirements for DCF computations. For example, investment bankers in the 1980s used computers “the size of rooms” to value a bond’s cash flows. Unlike simple P/E ratio arithmetic, DCF modeling requires much greater computing power.

During the 1990s, as technology dramatically evolved, and a new wave of public companies without earnings to evaluate dominated, DCF analysis grew in popularity. Without earnings to measure against, analysts focused on forecasting future cash flows.

Conclusion: Modern Valuation Tools

Despite advancements in valuation techniques and the vast amounts of data now available, the fundamental nature of markets remains unchanged—their function is driven by differing opinions and the inherent uncertainty of price dislocation. This is a core aspect of markets that no amount of information can resolve; it's what keeps markets dynamic and fluid.

Historically, the most adept investors have been those who could analyze information more effectively than their peers. This has held true from the earliest days of financial markets to the present, demonstrating that access to information alone is insufficient for success. Instead, the key differentiator has been the ability to derive insightful interpretations and make decisions based on that information.

Over time, technological advancements have progressively shifted the focus from mere data gathering to deeper analysis. Today, modern technologies empower investors to spend more time examining and understanding investment opportunities than ever before. This shift has not only made financial analysis more efficient but also more strategic, allowing investors to make more informed decisions with a richer contextual understanding of their investments.

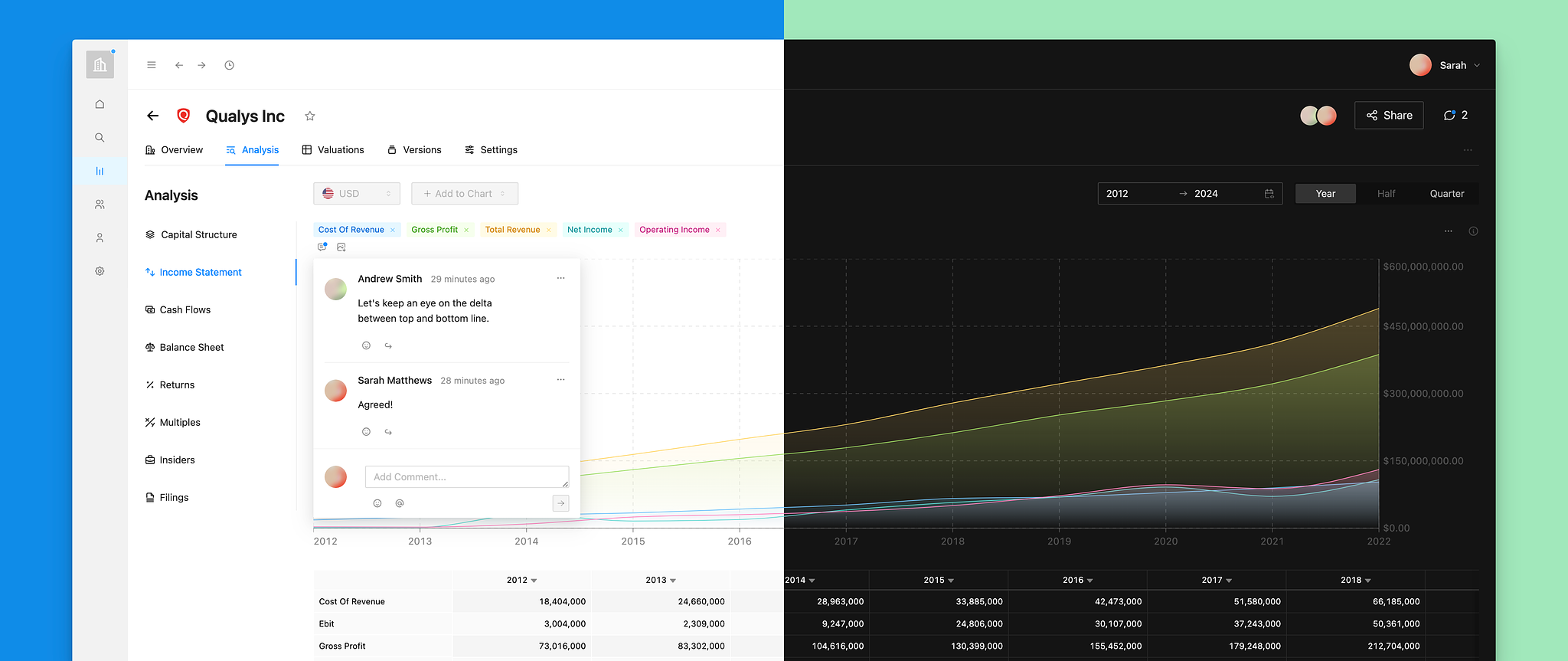

In this context, companies like Countercyclical represent a significant leap forward in the tools available to value investors. This investment platform has been meticulously designed to empower investors by scaling much of the traditional valuation process, particularly the labor-intensive aspects such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis. By simplifying these complex calculations, Countercyclical allows investors to dedicate more time to collaborative and strategic aspects of investment analysis.

Countercyclical is built for value-oriented finance teams of all sizes, offering a suite of tools that facilitate real-time collaboration, streamline the creation of extensive valuation models, and enable the swift sharing of insights. With features like customizable templates for scenario analysis on thousands of securities and integrated drafting tools for investment memos, Countercyclical ensures that investors can maintain focus throughout the due diligence process, enhancing both efficiency and depth of analysis.

As we look to the future, platforms like Countercyclical exemplify the next step in the evolution of financial valuation. They not only equip investors with powerful computational tools but also foster an environment where strategic thinking and collaboration are at the forefront of investment decision-making. This integration of technology with fundamental investing principles promises to refine further the art and science of value investing, ensuring that investors can navigate the complexities of modern markets more effectively than ever before.

Footnotes

[1]: Anne Murphy, ‘How to Speculate According to the Merchant Principle’

[2]: ‘Remarks on the Celebrated Calculations’ (1720)

[3]: Geoffrey Poitras, Valuation Of Equity Securities: History, Theory And Application, 2010

[4]: Janette Rutterford, ‘From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow: A History of UK and US Equity Valuation Techniques’ (February 2004)

[5]: Rutterford, 'From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow'

[6]: ‘Railroads: The First Big Business’, Encyclopedia

[7]: Library of Congress

[8]: Ralph L. Nelson, ‘The Merger Movement from 1895 – 1920’ (Princeton University Press, 1959)

[9]: Baruch Lev & Feng Gu, ‘Corporate Reporting Then and Now: A Century of “Progress”’, (June 2016)

[10]: F.W.H. Caudwell, A Practical Guid to Investment (1930)

[11]: Hilt, Jaremski, Rahn, 'When Uncle Same Introduced Main Street to Wall Street: Liberty Bonds & the Transformation of American Finance'

[12]: Irving Fisher, 'The Stock Market Crash and After' 1930

[13]: Rutterford, 'From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow'

[14]: Rutterford, 'From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow'

Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust on Unsplash